Human Lives Human Rights: One of the distressing incidents that happened years ago with the Iranian Hajj pilgrims was the tragic and cowardly killing of a young man named Abu Talib Yazdi, who was just 22 years old at the time. This individual was unjustly murdered, unrelated to any particular wrongdoing, causing profound shock among the Shiite community.

In December of 1943, a tragic and harrowing event unfolded during the Hajj rituals, sending shockwaves through Iran and the wider Shiite community. The incident revolves around the circumstances of December 10, 1943, when a 22-year-old individual named Abu Talib Yazdi, hailing from Yazd, was participating in the Hajj pilgrimage in Mecca with his family. While performing the circumambulation of the Kaaba, the intense heat and a full stomach caused him to feel nauseous. Seeking to preserve the sanctity of Masjid al-Haram’s ground, he held the edge of his Ihram garment to his mouth and vomited into it, carefully holding it to prevent from spilling onto the sacred ground.

Unfortunately, a portion of it inadvertently splashed onto the stones of Masjid al-Haram. This act led to his arrest by Saudi police officers who suspected his intentions of defiling the Grand Mosque. Alongside several Salafist Egyptians as witnesses, he was taken to a police station and subsequently brought before a judge. During that period, a number of Egyptians, alleged to have received funds from an external source as described in the book “Come with Me to Mecca,” provided testimony suggesting Abu Talib’s intent to desecrate the Kaaba. This testimony ultimately led to his arrest.

Regrettably, on the 12th day of Dhul-Hijjah, which coincided with the commemoration of the House of Saud’s rise to power in Saudi Arabia, King Abdulaziz arrived at the holy shrine with elaborate ceremonies. After conducting the midday and evening prayers, he proceeded to sign the death sentence for Abu Talib and then departed from the sacred premises.

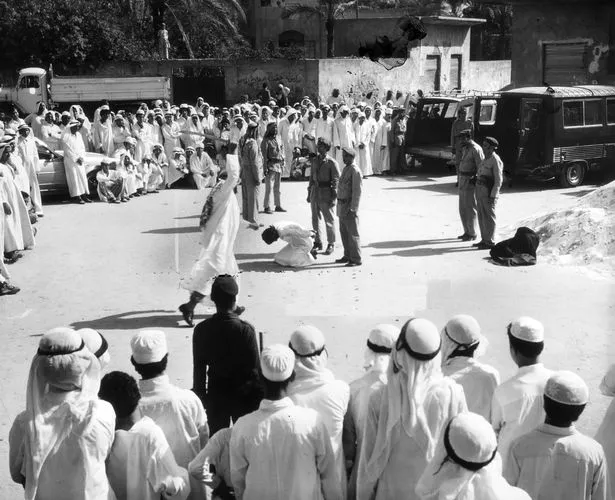

Misguided witnesses gave erroneous testimony, leading to the unjust verdict of an innocent pilgrim’s death. The following day, on the 14th of Dhul-Hijjah, he was publicly executed by sword on the street before a gathering of onlookers near Marwa. This severe punishment was meted out based on the false charge of defiling the sacred precincts of Kaaba.

Reports indicate that following the execution of Abu Talib Yazdi, a crowd assembled within Masjid al-Haram, expressing jubilation and exchanging congratulations over his killing. They targeted each Iranian pilgrim, hurling insults and issuing threats of violence. These behaviors triggered widespread apprehension and distress among Iranian pilgrims. They chose to steer clear of being alone and abstained from entering the mosque even when Sunni prayers were taking place. They adopted a heightened sense of vigilance as their guiding principle during sacred practices like prayer and circumambulation, all in a concerted effort to ensure their own safety.

In his memoirs, Mohsen Sadr al-Ashraf, an Iranian statesman known for his favorable relations with the Saudi court, recounts the events at Masjid al-Haram in the following manner: “During my personal Hajj pilgrimage in 1941, I observed a recurring nightly scene—a chair placed just outside the courtyard of Masjid al-Haram, with a preacher seated upon it. This preacher’s discourse consistently revolved around Shiites, commonly referred to as Rafizis, whom he denounced as polytheists. His calls resonated for the government to bar this congregation from entering the revered shrines of Mecca and Medina.

Another dimension of their prejudice was ethnic in nature, rooted in the perception held by Arabs that Iranians were non-Muslims. This, in turn, led to a lack of respect from Arabs toward those perceived as non-Muslims. In this atmosphere, Iranian pilgrims faced distressing mistreatment, enduring a form of humiliation that stood as one of the most degrading experiences.

Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab carried the philosophical tenets of Ibn Taymiyyah to Saudi Arabia, thereby establishing the Salafi perspective within the Saudi Sunni scholars. “Salaf” denoting the past, the adherents of Salafism positioned themselves as authentic adherents of historical Islam. Their assertion held that adhering to the ways of Islam’s inception was imperative, shunning the trappings of modern civilization. Furthermore, they held the view that Shias were apostates.

Evidenced by historical records, Iranian pilgrims encountered recurring insults from Salafis throughout the 1920s and 1930s. The Saudi monarch found it necessary to consistently appease the Salafis through financial means in order to secure his rule. In return, these Salafi factions refrained from critiquing the king’s opulent lifestyle and his affiliations with Western governments. This arrangement allowed the Saudi monarchy to avoid surpassing the boundaries of modern state reforms while maintaining its political power.

Recounting the incident, Abu Talib’s wife offers her perspective: Prior to entering the shrine, we had a meal at a nearby restaurant, and it’s possible that the food had spoiled. The combination of fatigue and the intense heat also contributed to the unfolding of this unfortunate event.

On the subsequent day, when the verdict was announced, a gathering assembled near Marwa. Abu Talib stood among the crowd, his hands bound, and as he wasn’t conversant in Arabic, he observed his surroundings with a puzzled expression. A police officer leaned in and whispered something into his ear, which later revealed the accusation against him (Talawith Bayt) and the subsequent penalty. However, he failed to comprehend the words and exhibited no noticeable reaction.

The executioner readied himself, delivering a blow from behind aimed at his neck. In a swift motion, Abu Talib instinctively jerked his head forward, resulting in only a minor wound. In that fleeting moment, he could only muster these words: “At last, you did what you intended to!” With a subsequent strike, the executioner’s sword severed his head. Abu Talib’s wife, his companion on this journey, also faced expulsion from Saudi Arabia and was compelled to return to Iran.

English newspaper report

On February 7, 1944, the Lancaster Daily Post, a newspaper published in England, featured an article titled “Iran Severs Relations with Ibn Saud.” In this context, the article made the following observation: A seemingly inconsequential act took place in a modest café in Mecca when a waiter, driven by greed, served food prepared from spoiled meat to his patrons. Little did he anticipate that this single incident would escalate into significant diplomatic strife between the two nations, Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Continuing, the newspaper expounds: Mecca, a revered destination for every Muslim, holds an aspiration for at least one pilgrimage in a believer’s lifetime. Yet, the war has curtailed this sacred journey for pilgrims from distant lands. Regardless, devout Muslims from various parts of Arabia, Iraq, and Iran continue to converge upon this city, fostering a thriving café culture. In the span of nearly two weeks, a contingent of Iranian pilgrims arrived in Mecca, finding lodging within a caravan inn. Tired and hungry from their Hajj journey and their visits to the Kaaba, their desire was for nourishing sustenance.

Regrettably, the avaricious actions of a waiter unfolded. Serving them goat meat that had possibly spoiled, these pilgrims unknowingly consumed contaminated food. Consequently, during their Hajj rituals within the confines of Masjid al-Haram, illness befell them. This sudden turn of events sent shockwaves among the thousands of present pilgrims. Swiftly, the authorities were summoned. These law enforcement officers hailed from the seventh Bedouin tribe of Mecca, an integral part of the realm of the renowned Ibn Saud, the leader of the Wahhabi movement. Their response was immediate and severe, driven by a desire to execute the foreigners who they perceived as defiling their religious sanctuaries.

These officers afforded no room for explanations. Their stance remained unwavering, for the act of vomiting within the sacred precincts of the Kaaba transgressed a boundary of unprecedented gravity. Such an affront warranted nothing except death as retribution for this unforgivable sin.

In an evening edition on that same day, the Mecca newspaper prominently featured the following headline on its front page: “Arrest of Abu Talib Irani: Plotting to Defile the Kaaba Foiled.” The report detailed that Abu Talib Irani, hailing from Ardakan, Yazd, and identified as an Iranian Shiite, had been apprehended for an alleged scheme to desecrate the Kaaba. Subsequently, his guilt was established, leading to a death sentence that received the official endorsement of King Abdulaziz Saud. The execution of this sentence was duly carried out as scheduled.

The article further noted that on the 13th day, Sheikh Ali Asghar Tehrani, one of the Iranian pilgrims, volunteered to conduct the burial of the deceased. Upon being informed by Saudi police authorities that the body was ready for this purpose, Sheikh Ali Asghar proceeded to the forensic doctor. There, he discovered Abu Talib’s head had been positioned upside down on his body and sewn in place. This practice, as explained, was rooted in Wahhabi beliefs wherein individuals involved in such criminal acts were interred with their heads inverted, signifying their distinct status on the Day of Judgment.

The execution took an even more remarkable turn, with a perplexing scene surrounding the deceased pilgrim’s body: an unexpected request for a fee to attach the head. Sheikh Ali Asghar Tehrani was informed that a sum of 65 Saudi Riyals was required to cover the cost of sewing the head back onto the body. In response, a visibly upset Sheikh Ali Asghar expressed his indignation, vehemently asserting that the responsibility for the payment should rest upon the individual who had orchestrated the execution.

After a heated exchange, the body was eventually relinquished to Sheikh Ali Asghar, albeit without the demanded payment. When preparations for burial commenced, the body underwent a ritual cleansing. However, the head was detached from the body once more, serving as a somber reminder of the macabre circumstances. Undeterred, Sheikh Ali Asghar undertook the task of interring the remains within Mecca’s Martyrs’ Cemetery, a solemn act performed in memory of the deceased pilgrim.

It became evident that the accusation of deliberate intent in this incident was a fabrication stemming from ingrained racial biases. Consequently, a wave of anger surged among Iranians, with the backing of the Iranian government. This transpired during a period where Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had ascended to the throne two years prior, while allied forces were still present in Iran. This timeframe also saw individualized Hajj journeys, not subject to governmental oversight. Interestingly, the Iranian government lacked an embassy in Saudi Arabia at the time, with pilgrimage-related matters falling under the purview of the Iranian embassy in Cairo.

Apart from Iran, various Iraqi cities also bore witness to Shiite demonstrations, decrying the Saudi government’s policies against their sect. This collective response underlined the widescale opposition to the anti-Shiite stance being pursued by the Saudi regime.

Upon the news of Abu Talib Yazdi’s tragic murder reaching global ears, a profound wave of anger, sorrow, and protest surged through the Shiite communities both in Iran and across the world. During this period, Ayatollah Sayyid Abu al-Hasan Isfahani, a preeminent Shia spiritual leader residing in Najaf, conveyed his sentiments to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi via a telegram. In his communication, he found the king’s silence on the matter unjustifiable and forcefully called for the case to be pursued and the perpetrators of this heinous act to be brought to justice.

In both Najaf and Karbala, the people made their voices heard through various conferences and protest marches. Within Iran, a nationwide period of public mourning was declared, with Quranic gatherings held in numerous cities to honor the memory of the deceased. The profound impact of this incident was tragically underscored by the passing of Abu Talib’s two sisters, who succumbed to the weight of their grief within a brief span of time.

The event reverberated in the media as Iranian newspapers, magazines, and Arabic publications extensively covered the incident. Amidst the coverage, the behavior of the Saudi government came under scrutiny, prompting discussions on the necessity for reform within the Hajj pilgrimage system and its custodial framework. Correspondence ensued between the Iranian government and its Saudi counterpart, conveyed through the Iranian ambassador in Egypt who also served as the political envoy to Saudi Arabia. These exchanges encompassed Iran’s official protest and the subsequent response from the Saudi authorities.

The book titled “Aahang e Hijaz,” showcased by the Islam and Iran Library, delves into a pivotal event that unraveled in Saudi Arabia in the year 1943, leading to a significant rupture in the relationship between Iran and Saudi Arabia during that era. Authored by Ayatollah Haj Seyyed Fazlullah Hijazi, whose life spanned until 1968, this autobiography offers a compelling account of historical significance.

A portion of this historical work narrates the poignant tale of an Iranian’s beheading within the confines of Mecca:

As the 13th of Dhul Hijjah dawned, we found ourselves within Masjid al-Haram during the afternoon hours. A palpable sense of upheaval gripped the crowd, with jubilant expressions among the Arabs and the sharing of a somber phrase, “mass murder, mass murder.” When interactions took place with Iranians, a disconcerting gesture emerged – the Arabs placed their hands around their throats, accompanied by menacing words predicting the slaughter of foreigners.

Amidst this tense atmosphere, our compatriots and I reached a consensus, departing from Bab Ibrahim and proceeding toward Safa. Yet, upon our approach to Shari Khana, a sizeable congregation had assembled near Bab Safa. There, a disconcerting revelation circulated: Abu Talib, the son of Hussain Yazdi Irani, who had been accused of desecrating the mosque, had met his end through beheading. Shockingly, the police were observed covering his blood with soil. As eyewitnesses, we solely bore witness to the disposal of the remains under these circumstances.

When darkness enveloped the surroundings and Maghrib and Isha prayers concluded, a sight unfolded in the Safa market – a group of individuals carrying a dead body. I sought insight from a comrade who was among the pilgrims: Whose remains are these? He somberly responded: The deceased is a young man who was unjustly beheaded today.

A cloud of trepidation and apprehension began to envelop the Iranian pilgrims. Directives were swiftly shared: Refrain from solitary ventures, avoid the mosque during communal prayers, exercise vigilance during acts of worship including prayer and circumambulation. The potential placement of a turbah (prayer stone) for prostration by ordinary Iranian individuals could inadvertently ignite unrest. Given the prevailing unrest and anxiety over the past two days, this cautionary approach was deemed paramount.

Subsequently, the Saudi government intervened, with a prominent role attributed to the Egyptians in orchestrating this tumultuous situation. However, an account published in the Umm al-Qari newspaper, the official weekly publication of Mecca, diverged from the prevailing narrative. The newspaper’s report presented a contrasting version of events: an Iranian pilgrim, by the name of Talib bin Hussain, stood accused of carrying impurity and inadvertently spilling it along the path of the Hajj circumambulation. Yet, upon conducting an inquiry and gathering information from credible sources, a different portrait emerged.

According to the investigation, it was established that Talib bin Hussain hailed from the Yazd province of Iran. His intention to perform the Hajj pilgrimage was marked by a sense of reverence and honor, without any indication of ill intentions towards the mosque or fellow pilgrims. It was acknowledged that he consumed a substantial meal, and on the 12th day, following his return from Mina, he entered Masjid al-Haram during the afternoon hours to embark upon the Hajj circumambulation. Unfortunately, it was at this juncture that an episode of vomiting unexpectedly overcame him.

Following the execution of Abu Talib, a robust exchange of correspondences unfolded between Iran and Saudi Arabia. In response to Iran’s formal grievance, Saudi Arabia penned a strongly worded letter that transcended the singular case of Abu Talib. The letter encompassed a sweeping accusation that implicated all Iranian pilgrims in defiling the sanctity of the sacred precincts. To bolster their standpoint, Saudi Arabia invoked select verses from the Quran, striving to substantiate the righteousness of their actions. Notably, an excerpt from the letter encapsulates the Saudi argument, citing a verse from Surah Hajj, verse 27: “The Quran says in this regard, whoever commits atheism and injustice in the House of God, we will punish him with a severe punishment.”

Iran’s retort took a different trajectory. The Iranian authorities maintained that Abu Talib’s act was born out of sheer necessity and a sense of urgency, attributing it to moments of inconvenience. Expressing bewilderment, Iran questioned the recurrent employment of Quranic verses in the Saudi communication, given the incongruity between the cited verses and the specific incident. Furthermore, Iran highlighted the unfortunate manner in which Abu Talib, their pilgrim guest, was treated by the custodians of the shrines. His neck was restrained, and his life was summarily ended without any display of mercy or compassion, an act that also disregarded the plight of his distraught wife. Iran further noted the peculiar nature of Saudi Arabia’s approach, using Quranic verses in their Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ argument as a veneer to obscure the gravity of the crime committed.

Upon Abdolhossein Hazhir assuming the prime ministerial role in 1948, tensions arose, exacerbated by accusations from clerical circles, particularly Ayatollah Kashani, asserting his opposition to Islam. To dispel these allegations, Hazhir embarked on a mission to reopen the Hajj pilgrimage, despite the prevailing discord between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Simultaneously, the Saudi Arabian king dispatched a letter to Iran’s sovereign, expressing a desire for the resumption of relations and implicitly extending an apology—a conciliatory gesture.

Responding to this overture, Hazhir swiftly initiated diplomatic efforts to reconcile the two monarchs. Adding a diplomatic touch, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi contributed to the restoration of amicable ties by presenting the Saudi Arabian king with a gold-framed sword and other historically significant gifts. This marked a rekindling of diplomatic relations.

Under Hazhir’s guidance, a designated official named “Ameen al Hujaj” (the protector of pilgrims ) was entrusted with the organization of Iranian pilgrims, solidifying the resumption of Pahlavi-era relations with Saudi Arabia. However, the perpetrators responsible for Abu Talib’s death remained unprosecuted, and his family received no reparation. The profound sorrow experienced by Abu Talib’s family was further compounded by the distressing detail that even in forensic procedures, his head was found sewn upside down onto his body.

This tragic episode resulted in a five-year hiatus in diplomatic relations between the Iranian and Saudi governments. Subsequent to this period, in 1948, the prime minister’s directive heralded the reestablishment of relations and the reopening of Hajj pilgrimage avenues. The renewal of communication and the resumption of Iranian pilgrimages was predicated on the mutual economic benefits sought by the Saudi government and the fervent desire of Iranians to partake in the Hajj rituals.

Thnnnxxx.