How frequently have terrorist attacks occurred over the last three decades in western Europe? Which countries stand out in terms of their vulnerability to these attacks? Who or what have been the principal targets for such attacks?

Before examining the evidence, let us define the terms and parameters of this commentary. Our data are drawn from Jacob Aasland Ravndal’s RTV Dataset (“Right-Wing terrorism and violence in Western Europe: Introducing the RTV Dataset”) and we apply his definitions of two concepts: terrorism and right-wing extremism.

By terrorism, we mean:

“[T]he threatened or actual use of force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion or intimidation.”

And, by right-wing extremism, we mean:

“… those who regard social inequality as inevitable, natural or even desirable. Most perpetrators of right-wing violence adhere to a far-right mix of anti-egalitarianism, nativism, and authoritarianism. These ideological constructs and the beliefs that are strongly associated with them – such as racism and conspiratorial thinking – produce a set of political and social groups considered as enemies of and legitimate targets for the far right.”

We should point out that the perpetrators of these terrorist attacks are typically small groups (e.g., the National Socialist Underground) or lone actors (Anders Breivik), who display varying levels of lethality, planning and organization. The data collection does not include mob violence, such as crowd attacks on immigrant or refugee hostels or encampments.

Frequency

As Graph 1 makes clear the overall trajectory of right-wing terrorist attacks over the years is upwards, with peaks and valleys to be sure. Despite the efforts of NGOs, the European Union and national law enforcement agencies, the frequency of radical right-wing terrorist attacks has increased over time.

It is a matter of some controversy among political analysts, but we should remind ourselves that this period of heightened right-wing violence also saw the rise in popularity of right-wing populist parties in the West European democracies, suggesting, but not proving, that we are dealing with the same general phenomenon. The label ‘backlash’ comes to mind, a reaction to mass immigration into Europe from developing nations, the Middle East, South Asia and Africa, both Northern and sub-Saharan.

Targets

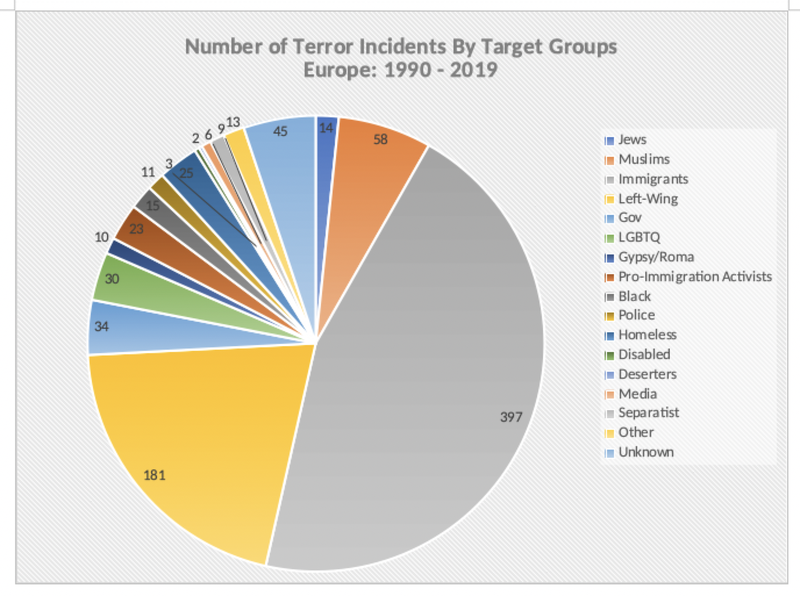

This judgement is reinforced when we identify the targets of right-wing terrorism.

The distribution of the frequency makes it clear that the substantial majority of right-wing terrorist attacks have been aimed at immigrants and Muslims (the two are not identical), along with Blacks and pro-immigration activists. Among other victims were the homeless, disabled, and LGBTQ individuals, and essentially defenseless targets.

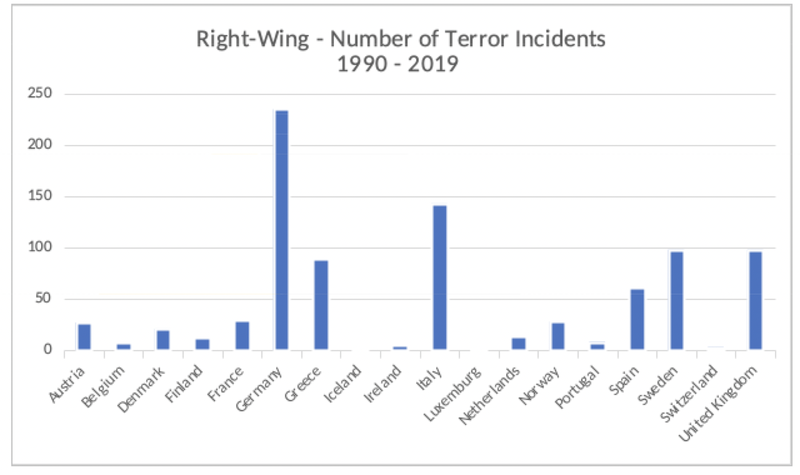

Most affected countries

The countries of western Europe varied in terms of how often they were the sites of right-wing terrorist attacks. As displayed in Table 3, Germany, Greece, Italy, Sweden, and the United Kingdom stand out.

If we were to impose a control for relative population size, two countries at opposite ends of the sub-continent, Greece and Sweden, stand out, ‘punching above their weight’ as it were. At first glance, the two countries appear to have little in common. Until recently, the Stockholm government has had a welcoming attitude towards immigrants. Athens has become increasingly hostile to people from Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East seeking entry to Europe via Greece and the short sea route from Turkey through the Aegean.

Despite these differences, the arrival of substantial numbers of foreigners has spawned a violent reaction. In Sweden, the Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM) formed on a region wide basis by neo-Nazis in 1997, has carried out terrorist attacks in Malmo and elsewhere. In Greece, Golden Dawn until it was recently banned and its leaders convicted for having committed violent crimes, was another neo-Nazi aggregation that likewise carried out terrorist attacks on refugee targets.

Measured by overall volume of right-wing terrorism, Germany and Italy, the two former World War II Axis powers, lead the way. Both Italy’s republican Constitution (1948) and the German Basic Law (194 9) prohibit the formation or reformation of a Fascist and Nazi party under any circumstances and under any guise. Both governments in Rome and Berlin possess the ability, via their judicial arms, to dissolve groups that express these anti-democratic values. And from time-to-time they have done just that (e.g., the New Order, Viking Youth). In the Federal Republic, for example, it is a crime to publicly display the swastika or other symbols of the Hitlerite dictatorship.

Despite decades of apparent success in promoting democratic political norms through the schools and constitutional prohibitions, older Germans and Italians have managed to pass along to at least some members of younger generations, nativist and xenophobic values that make them susceptible to new waves of right-wing terrorism.

A wider problem

We need to make two concluding observations. First, as a number of observers have pointed out, recent public opinion surveys of western Europeans indicate the region’s young people are becoming less supportive of democracy. Right-wing violence then might well be viewed not as an isolated phenomenon but as symptomatic of a wider malaise among younger Europeans.

Second, what the younger generations of right-wing extremists possess that older ones lacked is social media. The Internet has offered the young opportunities for instant communications across borders that their World War II grandparents could only dream of. This in turn has made possible the emergence of a growing transnational threat of a Euro-American radical right, with dreams of glory.

Professor Leonard Weinberg is a Senior Fellow at CARR and an Emeritus Professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada.