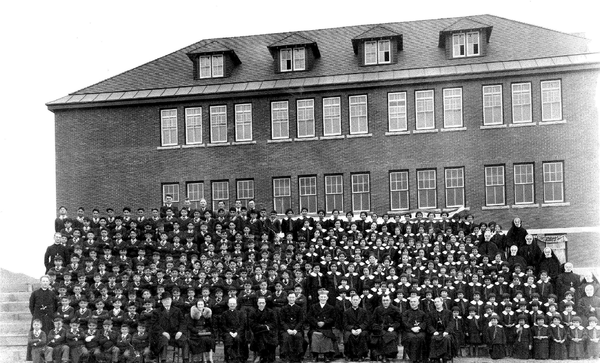

Human Lives Human Rights: From the 19th century until the 1970s, more than 150,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend state-funded Christian boarding schools in an effort to assimilate them into Canadian society. Thousands of children died there of disease and other causes, with many never returned to their families.

Nearly three-quarters of the 130 residential schools were run by Roman Catholic missionary congregations, with others operated by the Presbyterian, Anglican and the United Church of Canada, which today is the largest Protestant denomination in the country.

The Canadian government has admitted its role in a century of isolating native children from their homes, families and cultures, and that physical and sexual abuse was rampant in the schools, where students were beaten for speaking their native language.

That legacy of abuse and isolation has been cited by native leaders as a cause of alcoholism and drug addiction widely seen on reservations today.

Indigenous leaders have called it a form of cultural genocide.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called it “an incredibly harmful government policy that was Canada’s reality for many, many decades and Canadians today are horrified and ashamed of how our country behaved.”

He said the policy “forced assimilation” on the children.

What’s behind the discovery of the remains?

A National Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was set up as part of a government apology and settlement, issued a report in 2015 that identified about 3200 confirmed deaths at schools. While some died of diseases like tuberculosis amid the often-deplorable conditions, it noted that a cause of death for about half of them often was not recorded.

The Bosnian Serb government is indoctrinating children with denials of the 1995 genocide in Srebrenica of 8,000 Muslim men and boys, and wrecking attempts at reconciliation, the head of a U.N. court said in an interview.

Judge Carmel Agius, president of the court completing war crimes trials stemming from the breakup of Yugoslavia, added unhealed ethnic divisions in Bosnia were driving the younger generation away in their tens of thousands.

The 1992-95 Bosnian war claimed roughly 100,000 lives and left Bosnia deeply divided along ethnic lines, split into two autonomous regions joined by a weak central government.

The Serb member of Bosnia’s tri-partite presidency, Milorad Dodik, last year called the Srebrenica genocide “a fabricated myth”. He has also opened a student dormitory named after former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic, who is serving a life sentence after being convicted of genocide for Srebrenica.

The Bosnian Serb army seized the area on July 11, sending the women away in buses and transporting the men to dozens of execution sites. Their bodies were dumped in mass graves.

Mladic has appealed his conviction for genocide over Srebrenica, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

In 2018 Bosnian Serb authorities withdrew a 2004 report by their predecessors acknowledging the genocide and established a panel to review the number of victims.

“In this way the Serb Republic government wants to bring the truth about the suffering of Serbs…closer to the international community and historians, who when they write about these events one day, will have clear evidence that truth is not only what one side states,” Bosnian Serb Prime Minister Radovan Viskovic said.